Ask anyone old enough to remember travel before September 11 2001 and you are likely to get a hazy recollection of what flying was like.

There was security screening, but it nowhere near as intrusive. There were no long check-in queues. Passengers and their families could walk right to the gate together.

Overall, an airport experience meant far less stress.

That all ended when four hijacked planes crashed into the World Trade Centre towers, the Pentagon and a field in Pennsylvania.

The worst terror attack on American soil led to increased and sometimes tension-filled security measures in airports across the world. It also contributed to other changes large and small that have reshaped the airline industry — and made air travel more stressful than ever.

Two months after the attacks, President George W Bush signed legislation creating the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), which required that all checked bags be screened, cockpit doors be reinforced, and more federal air marshals be put on flights.

There has not been another 9/11 – nothing even close – but after that day, flying changed forever.

Security measures evolved with new threats, so travellers were asked to take off belts and remove some items from bags for scanning. Things that clearly could be wielded as weapons, like the box-cutters used by the 9/11 hijackers, were banned.

After “shoe bomber” Richard Reid’s attempt to take down a flight from Paris to Miami in late 2001, footwear started coming off at security checkpoints.

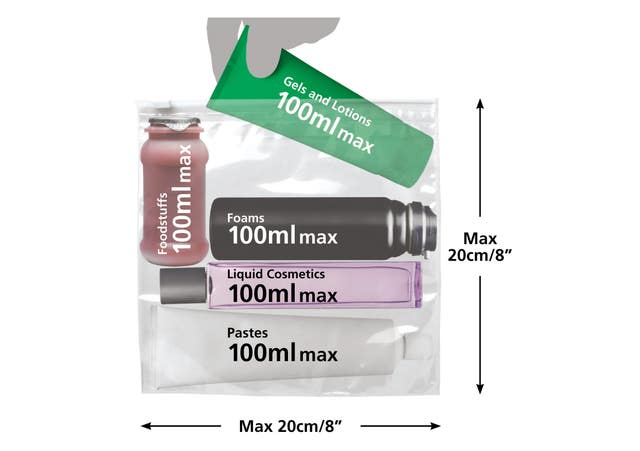

Each new requirement seemed to make checkpoint queues longer. To many travellers, other rules were more mystifying, such as limits on liquids because the wrong ones could possibly be used to concoct a bomb.

The long queues gave rise to “trusted traveller programmes” in which people pay a fee and provide certain information to pass through checks without removing shoes and jackets or taking laptops out of their bag.

But that convenience has come at a cost: privacy.

On its application and in brief interviews, people can be asked about basic information like work history and where they have lived, and they give a fingerprint and agree to a criminal record check.

Privacy advocates are particularly concerned about ideas that the TSA has floated to also examine social media postings (the agency’s top official says that has been dropped), press reports about people, location data and information from data brokers including how applicants spend their money.

More than 10 million people have enrolled in the US PreCheck scheme. The TSA wants to raise that to 25 million, with the goal of allowing officers to spend more time on passengers considered a bigger risk.

At the direction of Congress, the TSA will expand the use of private vendors to gather information from PreCheck applicants. It currently uses a company called Idemia, and aims to add two more — Telos Identity Management Solutions and Clear Secure.

Clear plans to use PreCheck enrolment to boost membership in its own identity-verification product by bundling the two offerings. That will make Clear’s own product more valuable to its customers, which include sports stadiums and concert promoters.

“They are really trying to increase their market share by collecting quite a lot of very sensitive data on as many people as they can get their hands on,” says India McKinney, director of federal affairs for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, an advocacy group for digital rights.

TSA administrator David Pekoske said: “We have allowed the vendors to bundle their offerings together with the idea that would be an incentive for people to sign up for the trusted traveller programmes.”

The TSA is testing kiosks equipped with facial recognition technology to check photo IDs and boarding passes. The kiosks will also pull photos taken when the traveller applied for PreCheck, Ms McKinney says. That concerns her because it would mean connecting the kiosks to the internet and potentially exposing the information to hackers.

Despite the trauma that led to its creation, and the intense desire to avoid another 9/11, the TSA has frequently been the subject of questions about its methods, ideas and effectiveness.

Critics, including former TSA officers, have derided the agency as “security theatre” that gives a false impression of safeguarding the travelling public. Mr Pekoske dismisses that by pointing to the huge number of guns seized at airport checkpoints — more than 3,200 last year, 83% of them loaded.

VIDEO: Our officers continue to discover a high number of firearms in carry-on bags. You must always pack your guns and ammunition in a checked bag. Watch the video for proper packaging guidance. If you have further questions reach out to @AskTSA right here on Twitter. pic.twitter.com/gSZoi9NRks

— TSA (@TSA) August 31, 2021

He also listed other TSA tasks, including vetting passengers, screening checked bags with 3D technology, inspecting cargo and putting federal air marshals on flights.

“Rest assured: This is not security theatre,” he says. “It’s real security.”

Several incidents highlight a threat the TSA needs to worry about — people who work for airlines or airports and have security clearance that lets them avoid regular screening.

— In 2016, a bomb ripped a hole in a Daallo Airlines plane, killing the bomber, but 80 other passengers and crew survived. Somali authorities released video they said showed the man being handed a laptop containing the bomb.

— In 2018, a Delta Air Lines baggage handler in Atlanta was convicted of using his security pass to smuggle more than 100 guns on flights.

— The following year, an American Airlines mechanic with so-called Islamic State videos on his phone pleaded guilty to sabotaging a plane full of passengers. Pilots aborted the flight during take-off.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel